If you’ve ever seen a jaguar, skull, or even a full car shimmering with thousands of tiny beads, you’ve likely met the dazzling world of Huichol (Wixárika) bead art. Beyond the sparkle is a deep story—pilgrimage routes in the Sierra Madre, sacred symbols like the deer and peyote, and a community that has adapted materials without losing its spiritual grammar.

This is a quick, curious tour through where that art comes from, why it matters, and how to appreciate it with respect.

Who are the Wixárika (Huichol)?

The Wixárika—often called Huichol in Spanish—are Indigenous communities centered in the Sierra Madre Occidental across today’s Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango, and Zacatecas. Their artistic traditions are not a trend; they’re part of a ritual life that includes pilgrimages, offerings, and visual languages carried across generations.

Museum collections and scholarship widely note that the best-known Huichol arts today are yarn paintings and beadwork, both saturated with traditional symbols and stories even as materials modernized.

Materials Evolve, Meanings Persist

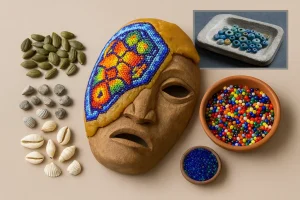

Before glass beads arrived through trade networks after the Spanish invasion, Wixárika artisans used seeds, shells, clay, bone, and stone to bead jewelry and ceremonial objects. In the modern era, imported glass micro-beads and commercial yarns became common.

The technique most people recognize—covering carved wood or forms with wax/resin and pressing in beads one by one—grew alongside markets for folk art in the 20th century. The key point: while the medium changed, the symbolic vocabulary remained deeply rooted.

Archaeology backs the broader story of bead circulation in colonial Mexico: excavations in Mexico City have recovered early glass beads, showing how quickly foreign materials moved through New Spain. That context helps explain why glass beads became available to Indigenous artists—and later, central to Huichol bead mosaics.

From Nierika to Contemporary Icons

Many people first encounter Wixárika art through yarn paintings derived from nierika, ritual tablets used to communicate with the divine. Yarn paintings migrated from strictly sacred contexts to gallery walls in the mid-20th century while retaining sacred motifs.

- Museums like the National Museum of the American Indian hold yarn paintings that reference creation myths, the birth of the sun, and shamanic visions—evidence that what seems decorative is actually visual theology.

- Beadwork followed a parallel path. Masks, bowls, and animal figures became vehicles for ancient patterns in a format that traveled easily to markets and exhibitions.

The “Vochol,” a Volkswagen Beetle covered with more than two million beads by Wixárika artists, became a global ambassador for the tradition, scaling up a devotional visual language to public-art size without losing its motifs.

The Visual Vocabulary: What the Symbols Say

While artists vary in style, several symbols recur with striking consistency:

Deer (Maxa): A messenger and sacred guide, often linked to peyote and revelation.

Peyote (Hikuri): The visionary cactus at the heart of certain rituals; a portal to communion with the divine.

Corn (Iyari/Maize): Life, sustenance, and reciprocity with the land.

Eagle, Serpent, Jaguar: Forces of protection, power, and cosmic balance.

Eyes, crosses, rhombi, and radiating lines: “Pathways” and portals, the geometries of seeing and being seen by the gods.

In bead art, the micro-mosaic technique turns these ideas into precise, pixel-like fields of color. The discipline is meditative: artists warm wax or use resin, then press each bead into place with a needle or fingertip, shaping shimmering topographies that read like prayers.

Markets, Museums, and the Ethics of Appreciation

As Huichol bead art moved from home altars to tourist stalls and museums, it faced the classic pressures of global craft markets: speed vs. quality, adaptation vs. stereotype, and fair pay vs. exploitation. Many artists collaborate with cultural institutions and ethical retailers; notable museum collections document lineages of makers and places of origin, from bowls and masks to large bead mosaics.

When you buy, look for provenance, the artist’s name, and context—small acts that protect artisans and reward the time and ritual knowledge embedded in each piece.

Technique at a Glance

Base: Carved wood, gourd, ceramic, or ready-made forms.

Adhesive: Beeswax mixed with pine resin (traditional) or modern resins for durability.

Beads: Glass micro-beads (chaquira) hand-placed in dense patterns.

Finish: Some works are purely decorative; others carry explicit ritual meaning and are treated accordingly.

Pro tip for collectors: Genuine pieces feel weighty for their size and show high bead density with crisp lines; cheaper knockoffs often have large gaps, repeated factory patterns, or no artist attribution.

Why It Captivates

Huichol bead art hits a rare trifecta: technical virtuosity, symbolic depth, and optical drama. It’s not just craft—it’s a cosmology mapped in glass and wax. The physics of light does the rest: thousands of bead facets catch and scatter illumination, so the work seems to breathe as you move around it.

You’re not only looking at an image; you’re participating in a ritual of seeing.

“Beads that Remember: How Tiny Glass Holds a Vast World”

Huichol bead art is proof that tradition isn’t a museum label; it’s a living practice that adapts materials while guarding meaning.

From seed beads to glass, from altar tablets to a beaded car, the Wixárika have shown that innovation can be faithful—and that a handful of color can carry a cosmos.